Part 1A: Introduction

The United States has the largest prison population and highest per-capita incarceration rate in the world. Both metrics have grown significantly in the past century, heavily outpacing population growth. Furthermore, “The US spends $270 billion annually funding the criminal justice system and maintaining prisons.” To incarcerated individuals, there is an approximate economic loss of $15 billion annually, wholly from tangible cost. With such high costs associated with imprisonment, it would be reasonable to expect the criminal justice system to carefully ensure a fair system when sentencing people to prison.

However, the fairness of the criminal justice system in the United States is currently being questioned. People convicted of the same crime can serve dramatically different prison sentences. In some instances, perpetrators convicted of heinous crimes, such as murder or rape, have faced little to no prison time. In other circumstances, convicted individuals have been sentenced to life in prison for petty theft, such as stealing nine dollars, a pair of hedge clippers, or even just a slice of pizza.

When sentencing someone to prison, it is important to consider any extenuating circumstances. Even when the outcome of a crime is similar, such as an individual dying, the sentence should reflect whether it was the result of an accident, negligence, or intent to do harm to another. Another key consideration is the likelihood of the defendant committing another crime, commonly known as recidivism.

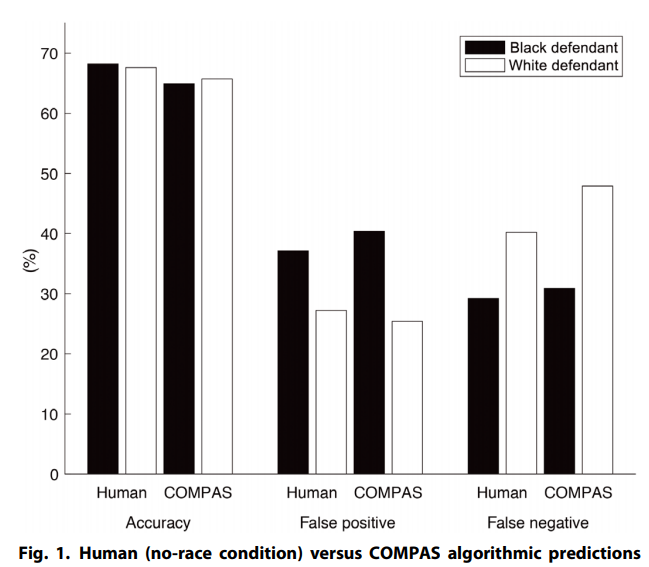

One major criticism of the United States’ prison system is that the extenuating circumstances are not evaluated fairly by judges and juries. It is difficult to avoid the influence of personal biases and opinions in determining a suspect's guilt, intent, and likelihood of recidivating. What if there was a way to limit the influence of human bias in sentencing while also accurately predicting whether an individual would recidivate? This was the promise of machine learning.

Part 1B: Recidivism in the United States

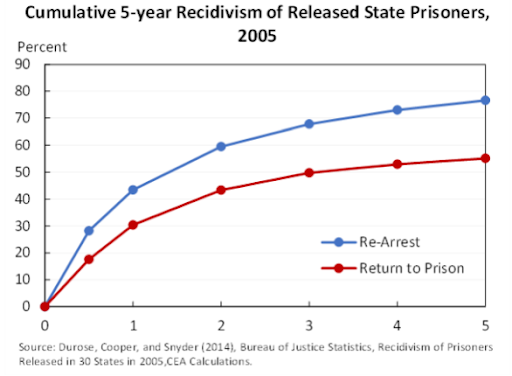

There is a high likelihood for convicted prisoners to recidivate. A U.S. Bureau of Justice report studied 401,288 released prisoners across 30 states in 2005 and found that 83% of released prisoners were arrested at least once after their release, with most arrests occurring within 5 years of release.