Part 1F: Get Curious

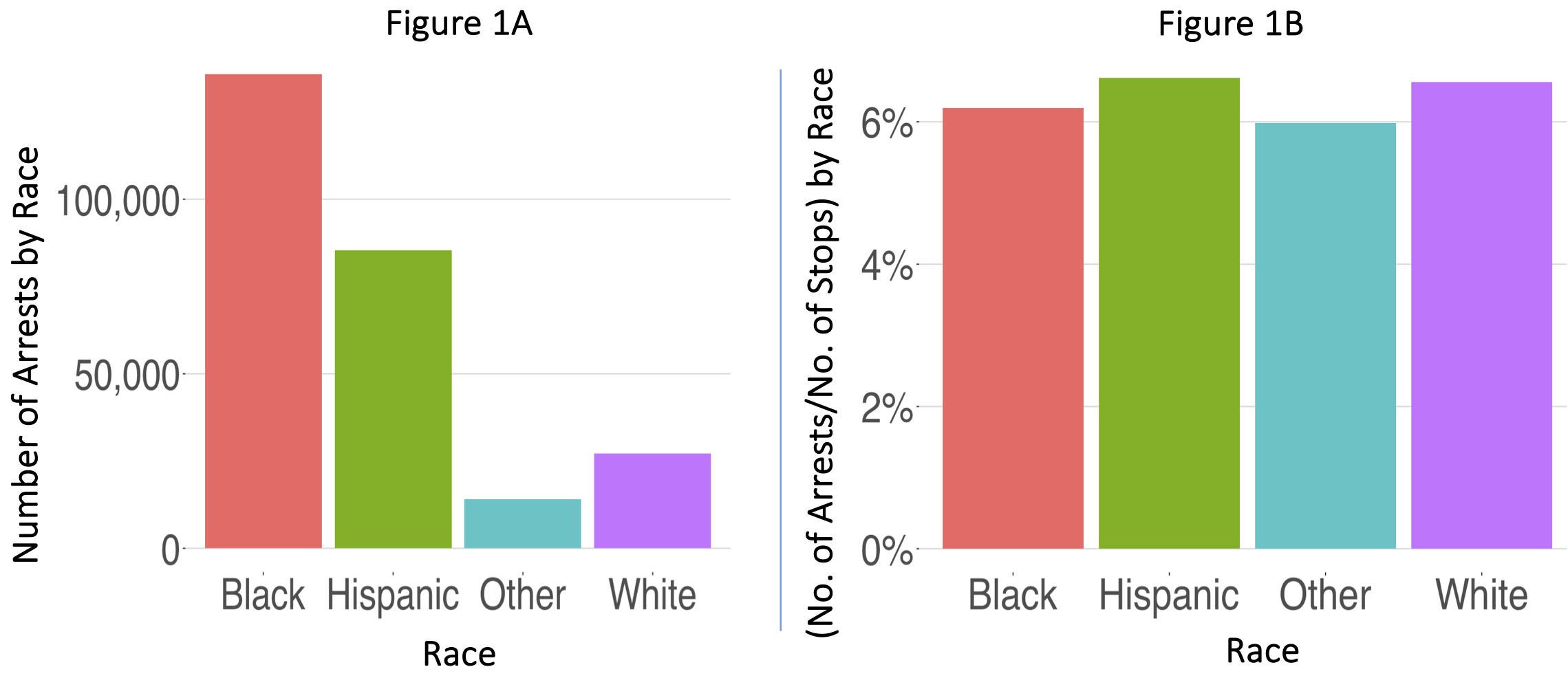

1. Which graph should be used to better understand the possible patterns of discrimination in the NYPD,

Figure 1A, 1B, or both? Briefly describe how each graph can contribute to addressing Focus Question 1.

How does the story change if both graphs are used?

2. Why is it important to consider the racial distribution of the entire city when looking at these

graphs?

3. When is it important to look at multiple graphs before drawing conclusions from a dataset?

4. In each report, a suspect is identified by the police as male, female, or unknown. Are there any clear

patterns related to the gender of the suspect? Assuming a male was stopped, is he more likely to be

arrested than a female? Do these patterns hold true across races? (Hint: try faceting by race.)

5. Which crime type tends to have the most arrests each year?

6. Develop your own question that could be answered with the above NYPD Bar Chart app. Write a one

paragraph answer to your question.

- Assume your audience already understands the source and context of the data.

- Include one or two graphs (cut and pasted from the app above).

- Clearly state your question, describe the variables in the graph(s), interpret your graph(s), and

discuss what conclusions you are able to draw from these graphs.

References

Shannon, Joel, Feb 2019, Adorable animals across the nation are making Super Bowl predictions, USA Today.

https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2019/02/03/animals-predict-super-bowl-outcome/2756507002/